Every day, American news outlets collectively publish thousands of articles. In 2016, according to The Atlantic, The Washington Post published 500 pieces of content per day; The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal more than 200. “We’re all consumers of the media,” says Duncan Watts, Stevens University Professor in Computer and Information Science. “We’re all influenced by what we consume there, and by what we do not consume there.”

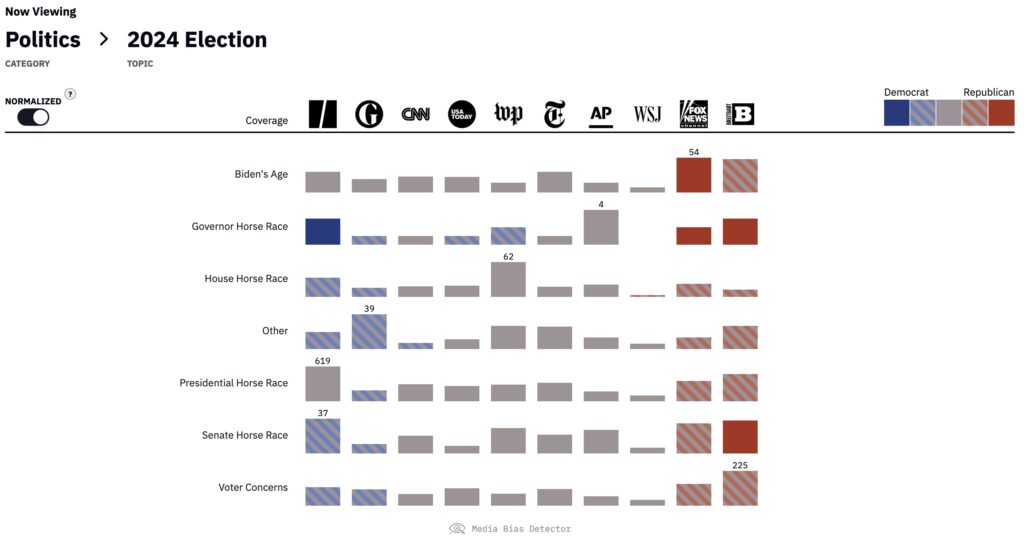

Today, the Computational Social Science Lab (CSSLab), which Watts founded and leads, launched the Media Bias Detector, providing media consumers an unprecedented level of detail in understanding how news outlets from across the ideological spectrum stack up against one another on topics as varied as the presidential race, social media and climate change.

By selecting topics and publication names from simple drop-downs, visitors to the Media Bias Detector can see exactly how different publishers covered particular topics during specific time periods — easily learning, say, how many stories The New York Times has published in the last six weeks about Joe Biden’s age, as opposed to Donald Trump’s, or how often Fox News covered climate change during last week’s heat wave compared to CNN. “Our goal is not to adjudicate what is true or even who is more biased,” says Watts, who also holds appointments in the Wharton School and the Annenberg School for Communication. “Our goal is to quantify how different topics and events are covered by different publishers and what that reveals about their priorities.”

In Watts’ view, media bias isn’t just the manner in which a publication covers a topic — the language used, the figures quoted — but also the topics that publications choose to cover in the first place, and how frequently. “The media makes a lot of choices about what goes public,” says Watts, “and that dictates the political environment.” Unfortunately, that data has been extremely hard to keep track of, due to the volume of daily news stories, and the time and expense associated with reading and classifying those articles.

Until now, unearthing media bias in this level of detail has been impossible to achieve at scale, but the CSSLab realized that artificial intelligence (AI) could augment the efforts of human researchers. “We’re able to classify text at very granular levels,” says Watts. “We can measure all kinds of interesting things at scale that would have been impossible just a year or two ago; it is very much a story about how AI has transformed research in this area.”

Everyone can read only so many articles from these publishers every day. So they have local views, based on where they stand. These AI tools elevate us so we can see the entire landscape

Amir Tohidi, postdoctoral researcher, CSSLab

On a daily basis, says Amir Tohidi, a postdoctoral researcher in the CSSLab, the Media Bias Detector accesses the top, publicly available articles from some of the country’s most popular online news publications, and then feeds them into GPT-4, the large language model (LLM) developed by OpenAI that underlies ChatGPT, the company’s signature chatbot.

Using a series of carefully designed prompts, which the researchers rigorously tested, GPT-4 then classifies the articles by topic, before analyzing each article’s tone, down to the level of individual sentences. “For every sentence,” says Tohidi, “we are asking, ‘What’s the tone of this sentence? Is it positive, negative, neutral?’” In addition to those sentence-level measurements, the researchers also use AI to classify the article’s overall political leaning on a Democrat/Republican spectrum.

In other words, the Media Bias Detector essentially maps America’s fast-changing media landscape in close to real time. “We are giving people a bird’s-eye view,” says Tohidi. “Everyone can read only so many articles from these publishers every day. So they have local views, based on where they stand. These AI tools elevate us so we can see the entire landscape.”

In order to ensure the Media Bias Detector’s accuracy, researchers have incorporated human feedback into the system. “The beauty of it is that we incorporate a human in the loop,” says Jenny S. Wang, a predoctoral researcher at Microsoft and member of the CSSLab. “Because LLMs are so new, we have a verification process where research assistants are able to review an LLM’s summary of an article and make adjustments.”

Everyone has their own sense of what leaning these different publishers have. But no one has just looked at all the data. Powering these analytics at scale has never been done before.

Jenny Wang, predoctoral researcher, CSSLab

To validate the use of AI, the researchers also compared the system’s outputs to those of expert human evaluators — doctoral students with backgrounds in media and politics. “The correlation was really high,” says Yuxuan Zhang, a data scientist at the CSSLab. On some tasks, Zhang adds, GPT-4 even outperformed its human counterparts, giving the CSSLab confidence that AI could be incorporated into the process to achieve scale without significantly losing accuracy.

Zhang, a recent Penn Engineering master’s graduate in Biotechnology and Data Science, draws regularly on what he learned in the natural-language processing course taught by Chris Callison-Burch, Associate Professor in CIS, who is a consultant for the Bias Detector. “I worked as a head teaching assistant in that course,” says Zhang, “which is really an important tool for our lab, because everything in computational social science is related to natural-language processing.”

Building on Penn Engineering’s expertise in AI — the School recently announced the Ivy League’s first undergraduate and online master’s degrees in engineering in AI — the Media Bias Detector will provide an unprecedented opportunity for anyone to understand the subtle ways that bias manifests itself in the media.

“Everyone has their own sense of what leaning these different publishers have,” says Wang. “But no one has just looked at all the data. Powering these analytics at scale has never been done before.”

Try the Media Bias Detector yourself.

This research project was conducted by the Computational Social Science Lab, which bridges the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science, the Wharton School, and the Annenberg School for Communication, and was generously supported by Richard Mack (W’89).